In more than 20 years of working in the IT security industry, I’ve helped literally hundreds of companies build and mature their security programs. With some notable exceptions, when my team comes in to help out, these programs range from ineffective to completely nonexistent.

In many cases, there are too few security personnel trying to do too much with too little support (and money). My guess is that might have been the case at companies like Marriott, MGM Grand, Twitter, and Nintendo in the past year; not enough guards standing outside some of the world’s greatest treasure rooms of personal information and identity data.

If I’m being honest with myself, the only surprising aspect of these data breaches is that they weren’t worse. When it comes to U.S. consumers’ sensitive data, and breaches of that data, there are three main forces at play:

- Corporate America is ignoring its security obligations

- The federal government is unable to legislate regulatory protections for consumer data or to enforce existing regulations

- Consumers are not punishing corporations who lose their sensitive information

In the past decade, corporate America has made little progress toward better security:

- Security managers still report to technology executives, who view security as costly, disruptive, and less critical than operations

- Hackers are still the focus – not the data itself, nor the people managing it

- Senior executives are unaware of security risks or unwilling to take action

- Security budgets aren’t focused on training or supporting security personnel

- There’s little or no long-term strategic planning for security

The security landscape in regulated industries is cloudy in part because federal, state, and industry regulations don’t actually protect or secure sensitive data. And, they conflict with one another. What enforcement does occur for these regulations is largely symbolic.

Regulators and regulated companies continue to share a “checkbox” mentality about security – one that doesn’t examine the veracity, efficiency, completeness, or resilience of security controls. Said another way, it’s great you’ve got an encryption solution purchased – but have you deployed it to any laptops? Can you detail what sensitive data is on those encrypted laptops?

Compliance does not equal security, much like having a gym membership doesn’t mean you’re more fit.

The hard questions companies should be asking about their data aren’t contemplated by existing security frameworks: how to classify data, whether it needs to be stored, how long it should be kept, who should have access, how it’s backed up and archived, whether and how it’s encrypted, where it goes both in-network and in the Cloud, etc. Often the answers to these questions don’t exist because organizations don’t know where to start.

Meanwhile, consumers are enabling politicians and corporations to continue this quiet catastrophe of data breaches. TJX, the parent company of retailer T.J. Maxx, is responsible for one of the largest credit card data breach on record.

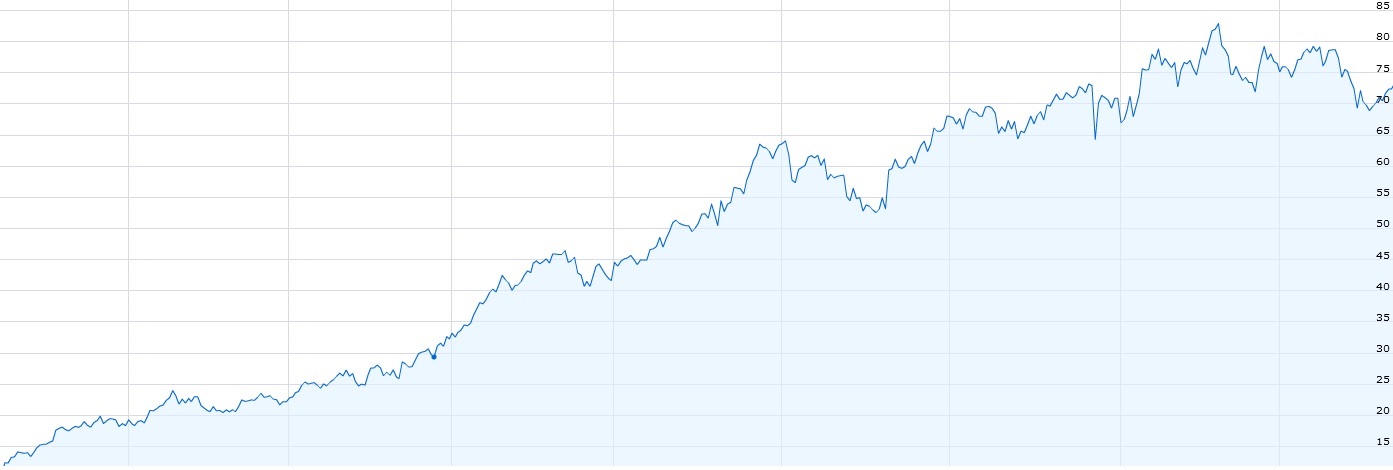

In 2007, between 45 and 94 million credit card numbers were stolen from T.J. Maxx. It cost them roughly a quarter of a billion dollars in breach-related spending to set things right, but their stock price never really suffered over the past decade:

TJX has grown to be one of the largest and most profitable retailers in the world, ranked #87 on the Fortune 500 list with revenues in excess of $33 billion.

The same story has played out with other retailers (Home Depot, Target), healthcare players (Anthem, Magellan, Tricare), tech giants (Yahoo!, EBay), media companies (Sony Pictures Entertainment), and financial services firms (JPMorgan Chase, Heartland Payment Systems, Citibank) who emerged basically unscathed from spectacular consumer data breaches.

I’m deeply cynical about data breaches and the organizations who “suffer” them. For many (if not most), it has been cheaper to ignore, underspend, and underdeliver on security protections, hoping they don’t get compromised and don’t have to publicly disclose such failures — than to proactively build defenses and resiliency.

I expect more and larger data breaches in the coming years. Whatever pretense of data privacy American consumers have insisted on, with regard to their personal identities, finances, and activities, is long gone and never to return.

Instead of playing (and losing) an arms-race game with hackers and cyber-criminals, we should be pulling back, focused on the sensitive data assets that our businesses, economies, and lives depend on. Otherwise, we’re just doing the same old things and expecting different results.

I hold out hope that individual companies can move the needle toward more mature security programs — placing information governance and data protection at the heart of their efforts.